When A Rabbi Makes Ukrainian Wedding Bread

Lubow Wolynetz, Folk Art Curator at the The Ukrainian Museum in NYC, graciously welcomes a group of 20 participants into a utilitarian classroom adjacent to a small kitchen. Plastic place mats sit on the tables in front of each person. At the back of the room, fanciful, shellacked Ukrainian wedding breads, known as korovai, inspire possibilities for our own baking. I’m there to deepen my research about Jewish celebratory breads, especially about Jewish bridal breads.

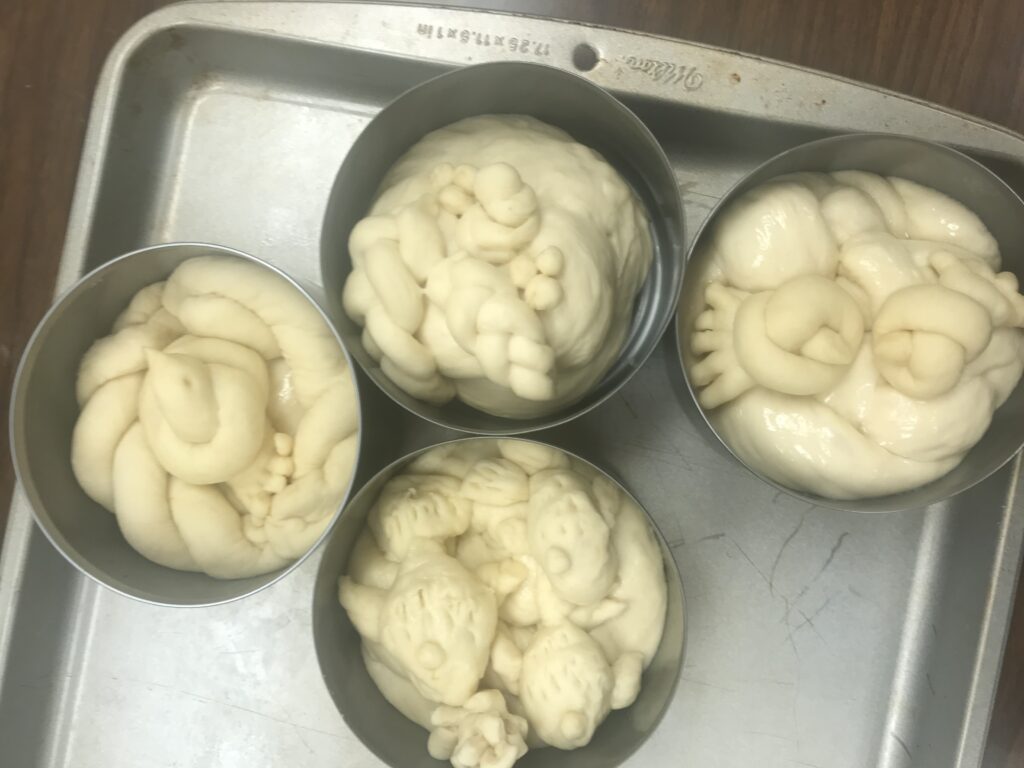

Soon, prepared dough will be distributed so that we can design our own mini-korovai. But first, Wolynetz shares the rich background of Ukrainian customs for wedding breads. Ritual and belief thoroughly mix into them, possibly stemming as far back to the 16th Century. These doughy creations manifest hopes for fertility, prosperity, and preservation of the community. Korovai also serve as welcome breads to mark life’s liminal moments. Wolynetz explains that you can’t control the weather, or when or to whom you’re born, or when and how you die, but you can control a wedding and its breads. This reliance on breads for celebration in Ukraine make sense given its reputation as the breadbasket of Europe. Celebratory breads for many occasions in many places preceded the fast rising cakes of the industrial period that we now take for granted.

Prior to the Wedding

Actually, Ukrainian weddings depend on several breads, not only korovai. A bread in the shape of a comb might be sent from the groom’s home to the parents of the bride. This represents the daughter’s work performed in her mother’s home weaving the flax and hemp. Also, a bread baked with two eggs (get it?) accompanies a formal dinner hosted by the groom’s parents. A bride and her brides-maids deliver yet another version, kolachyky or small round breads, to invite guests in the village to the wedding.

For the Wedding

Special rules apply to the bakers as well as to the baking. The korovai for the wedding–enriched with eggs, butter, and milk– relies on several elements that emphasize the number seven. The mother of the bride selects seven happily married women (known as korovainytsi) who contribute flour from seven mills, eggs from seven chickens, water from seven wells. Before starting, the seven bakers have to wash their hands and say a prayer. (The biblical passage…“The one with clean hands and a pure heart” from Psalm 24:4 comes to mind.) One of them makes the sign of the cross over the dough and the oven. They cannot gossip or say anything negative. Instead, they often sing an assortment of wedding songs to instruct the bride about ideal relationships, including with her future mother-in-law. The round base of the bread suggests the sun of pre-Christian offerings to a sun god. A braid around the base of the bread evokes a generational chain, unbreakable bonds, and everlasting life. A happily married man places the korovai gently into the oven.

After the baking, toothpicks attach decorations made from “dead or non-edible dough” tree in various shapes and configurations: branches, roses, birds, and more. They convey messages about love, faithfulness, life, luck, and more.

Multiple breads also feature at the wedding. The korovai is displayed at the church altar and during the wedding the feast. Family members decorate a symbolic wedding tree with ribbons, gilt, and herbs. It is carried into the church by the best man and then to the wedding feast to be placed inside a bread on a special table. At the beginning of the meal, the parents bless the couple with a kolach circular braided bread topped by a salt container. At the end of the meal, the bride and groom cut the korovai, sometimes vying for largest piece to claim the role of the boss of the family. Guests receive pieces to eat and to take home with them. Other breads–such as cone or acorn shaped syshky or round breads with cones in the center–might also have been gifted to guests.

After the wedding

When the groom enters the bride’s home, she holds up a dyveni bread. Its large hole allows her to focus carefully on the groom, to look into the future to their happiness, to identify the bride as the best. For the morning after the wedding, there’s yet another bread, this one laced with strips of dough into a lattice, sometimes with coins baked inside, birds decorating each grid of the lattice.

Fortunately, at the workshop we did not have to follow the rules of seven. We just focused on fashioning our own korovai, having fun with the imaginative symbols. These several Ukrainian breads prior, during, and after weddings connect the living organism of dough with life’s forces. This appetite for fresh, puffy, celebratory breads at weddings signal favor and fortune for newlyweds.

Recent Posts

-

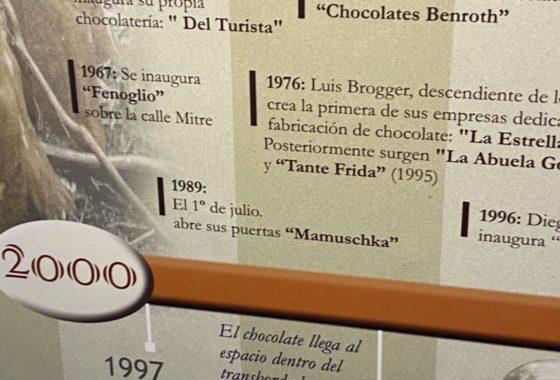

On the Chocolate Trail in Bariloche, Argentina

In March, Mark and I finally extended our chocolate trail explorations in celebration of our special anniversary to Bariloche…via Miami, Buenos Aires, Ushuaia, Antarctica, and Buenos Aires again. There were international flights, a cruise, a couple of domestic flights to get there. All of the travel was amazing, but Bariloche, sometimes called the chocolate capital

Read more › -

Sunday Yeast Polemics: On the Bread Trail

Leavened bread or not? While some of us may think of Passover, the question applied to Eucharistic bread and created significant division in the early Christian Church. The leavened bread for Sunday use was often baked at home by women. Over time, preferences shifted to clergy, church-produced, breads… and, the Eastern Orthodox Church preferred a

Read more › -

Sweet Treat: Chocolate and the Making of American Jews

You may wonder: how did chocolate help define American Jews? Through chocolate, we see that Jews were part of America since its earliest days. Well, since 1701 at least, Jews in the Colonies made part of their living through chocolate. Several Sephardim, leaders of their New York and Newport Jewish and secular communities, participated in

Read more › -

How About Some Uterus Challah?

When Logan Zinman Gerber felt enraged about the loss of reproductive rights in the U.S., she baked challah. Not any challah. She shaped it into a uterus. It wasn’t long after the birth of her daughter that Gerber, a longtime challah baker and staff member of the Religious Action Center of the Reform movement, considered

Read more ›

Some Previous Posts

(in alphabetical order)

- "Boston Chocolate Party" Q&As with Deborah Kalb

- 2022 Media for The "Boston Chocolate Party"

- A Manhattan synagogue explores the rich, surprising history of Jews and chocolate

- About Rabbi Deborah Prinz

- Baking Prayers into High Holiday Breads

- Boston Chocolate Party

- Digging into Biblical Breads

- Exhibit Opens! Sweet Treat! Chocolate & the Making of American Jews

- For the Easiest Hanukah Doughnuts Ever

- Forthcoming! On the Bread Trail

- Funny Faced Purim Pastries

- Good Riddance Chameitz or, The Polemics of Passover's Leaven

- How About Some Uterus Challah?

- Injera*

- Jewish Heritage Month: Baseball & Chocolate!

- Matzah - But, the Dough Did Rise!

- Plan a Choco-Hanukkah Party: 250th Anniversary Tea Party

- Prayers Into Breads

- To Shape Dough: A Trio of Techniques

Archives

2025

▾- All

2024

▾- January

- February

- March

- May

- July

- All

2023

▾- March

- April

- May

- June

- August

- November

- December

- All

2022

▾- February

- April

- November

- December

- All

2021

▾- March

- April

- October

- November

- All

2020

▾- April

- May

- June

- October

- December

- All

2019

▾- January

- February

- April

- May

- July

- August

- September

- October

- December

- All

2018

▾- February

- March

- April

- May

- July

- September

- October

- November

- December

- All

2017

▾- January

- February

- March

- July

- September

- October

- November

- December

- All

2016

▾- January

- February

- March

- May

- July

- August

- October

- November

- All

2015

▾- January

- February

- March

- May

- June

- July

- September

- November

- All

2014

▾- February

- April

- May

- June

- August

- September

- November

- All

2013

▾- March

- April

- May

- June

- July

- September

- November

- All

2012

▾- January

- February

- March

- April

- September

- October

- November

- December

- All

2011

▾- April

- July

- August

- October

- November

- All

2010

▾- January

- February

- April

- July

- August

- September

- October

- All

2009

▾- January

- June

- July

- August

- October

- All

2008

▾- August

- September

- October

- November

- All

2007

▾- January

- June

- July

- All

2006

▾- November

- December

- All