Good Riddance Chameitz or, The Polemics of Passover’s Leaven

Israel’s Health Minister Nitzan Horowitz recently reminded Israeli hospitals of the 2020 ruling of the High Court of Justice that permitted hospital visitors and patients to bring chameitz (leavened foods) into hospitals. In protest Idit Silman, MK from the Yamina party, resigned from the government over the the ruling, almost toppling the coalition even though food served by the hospitals would remain Kosher for Passover. This is just one more example of the polemics of leaven, the controversies that have beset leaven in Jewish settings since biblical times.

Supreme efforts have eliminated chameitz during Passover wherever Jews have lived. Matzah mania begins as soon as Purim ends, a full month prior to Passover. A Ladino song puts it this way: “Purim has come and before you turn around Passover is here.” There’s barely enough time to eat the leftover hamantashen, use up the yeast and flour, and locate Passover goods. Anything and everything to avoid chameitz leaven or yeasted products.

Through thick and thin, whether crisp or soft, families and communities shared a common commitment to getting that matzah just right. Stories of Jewish communities collected by Jennifer Abadi for her cookbook Too Good to Passover reflect dozens of handmade matzah traditions. For instance, Baghdadi Jews living in Shanghai prepped a crispy version of 12-inch circles with slight curves from the rounded oven walls, as did Jews in India, Lebanon, and Salonika. In India it was stored in a sheet hung from the ceiling. Ladino calls crisp matzah torta cencenya. The sect of Karaite Jews–believers in Torah-only Judaism from Egypt–prefer a crispy matzah with coriander seeds called korsa. Iranian soft matzah could be as tall as a child. In Algeria matzah was a ¼-½ inch thick with lacy designs. While crisp matzah could last the week, Bukharian, Iraqi, North African, Egyptian, Yemenite, and Sephardi Jews still make soft matzah daily and it may be purchased on line.

In Ethiopia matzah was prepared at home during the week, pierced with a fork to minimize the rise. That kita also served to plate the meal. Long, rectangular Egyptian matzah could be pre-ordered from a special oven in Cairo. Portuguese matzah makers wore clean white robes and baked on bricks. Small Jewish communities in Greece used ovens in synagogue courtyards. The 600-year-old community of Pitigliano, Italy, schlepped equipment down a hidden passageway to an underground oven where families produced their own matzah and other Passover baked goods. Throughout Southern Italy, former synagogues, now churches, still contain large, dome-shaped, ceramic matzah ovens. New York’s Shearith Israel Synagogue’s sexton or shamash supervised production by a local Christian baker, maintaining a monopoly on distribution throughout the 17th and 18th centuries.

Matzah eventually became industrialized into the crisp cracker many of us consume today. In truth, however, matzah was not a failed bread or a mishap on the trek out of Egypt. Matzah was a common flatbread in the ancient world, referred to at least three times in the Bible, each mention unconnected with Passover. (Genesis 19:3, Judges 6:19, I Samuel 28:24). Furthermore, despite the tradition’s insistence, the dough did rise during the Jews’ escape from Egypt. It had to have risen: Learn more about this mystery in the forthcoming On the Bread Trail…

Recent Posts

-

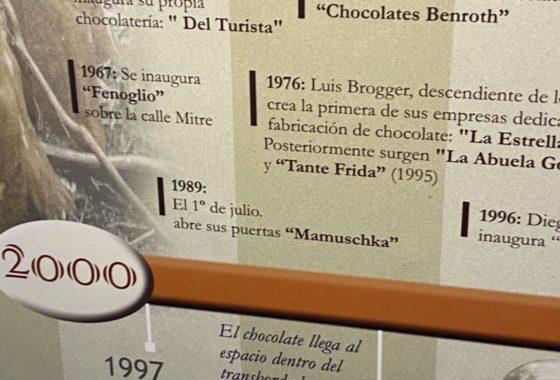

On the Chocolate Trail in Bariloche, Argentina

In March, Mark and I finally extended our chocolate trail explorations in celebration of our special anniversary to Bariloche…via Miami, Buenos Aires, Ushuaia, Antarctica, and Buenos Aires again. There were international flights, a cruise, a couple of domestic flights to get there. All of the travel was amazing, but Bariloche, sometimes called the chocolate capital

Read more › -

Sunday Yeast Polemics: On the Bread Trail

Leavened bread or not? While some of us may think of Passover, the question applied to Eucharistic bread and created significant division in the early Christian Church. The leavened bread for Sunday use was often baked at home by women. Over time, preferences shifted to clergy, church-produced, breads… and, the Eastern Orthodox Church preferred a

Read more › -

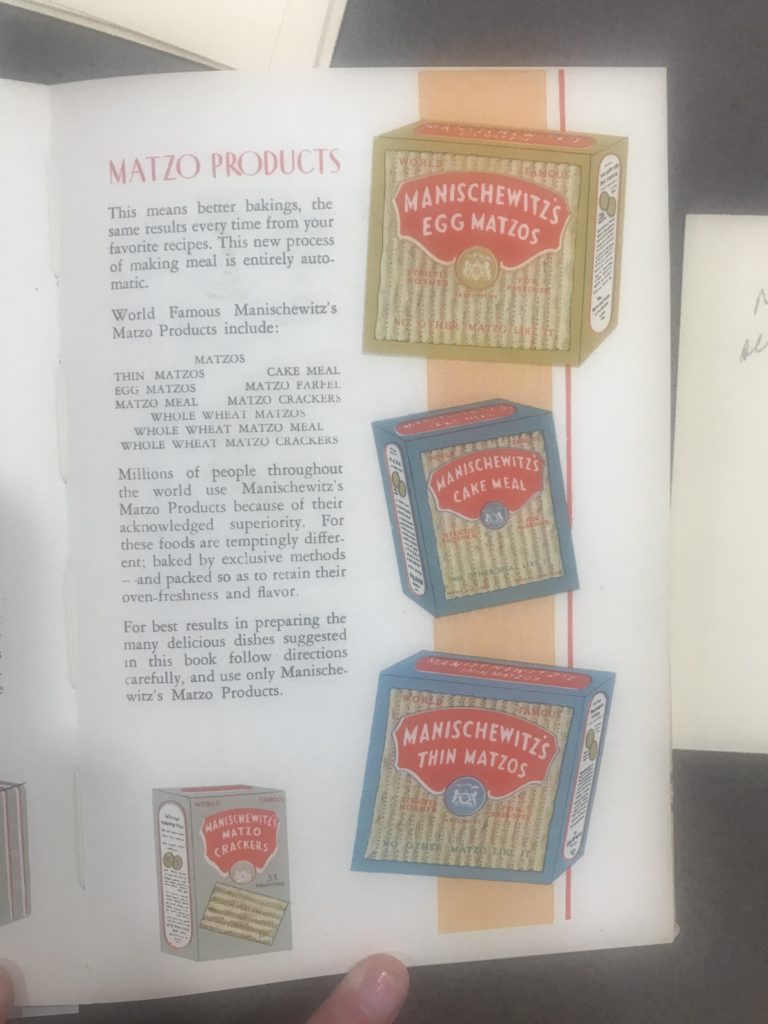

Sweet Treat: Chocolate and the Making of American Jews

You may wonder: how did chocolate help define American Jews? Through chocolate, we see that Jews were part of America since its earliest days. Well, since 1701 at least, Jews in the Colonies made part of their living through chocolate. Several Sephardim, leaders of their New York and Newport Jewish and secular communities, participated in

Read more › -

How About Some Uterus Challah?

When Logan Zinman Gerber felt enraged about the loss of reproductive rights in the U.S., she baked challah. Not any challah. She shaped it into a uterus. It wasn’t long after the birth of her daughter that Gerber, a longtime challah baker and staff member of the Religious Action Center of the Reform movement, considered

Read more ›

Some Previous Posts

(in alphabetical order)

- "Boston Chocolate Party" Q&As with Deborah Kalb

- 2022 Media for The "Boston Chocolate Party"

- A Manhattan synagogue explores the rich, surprising history of Jews and chocolate

- About Rabbi Deborah Prinz

- Baking Prayers into High Holiday Breads

- Boston Chocolate Party

- Digging into Biblical Breads

- Exhibit Opens! Sweet Treat! Chocolate & the Making of American Jews

- For the Easiest Hanukah Doughnuts Ever

- Forthcoming! On the Bread Trail

- Funny Faced Purim Pastries

- Good Riddance Chameitz or, The Polemics of Passover's Leaven

- How About Some Uterus Challah?

- Injera*

- Jewish Heritage Month: Baseball & Chocolate!

- Matzah - But, the Dough Did Rise!

- Plan a Choco-Hanukkah Party: 250th Anniversary Tea Party

- Prayers Into Breads

- To Shape Dough: A Trio of Techniques

Archives

2025

▾- All

2024

▾- January

- February

- March

- May

- July

- All

2023

▾- March

- April

- May

- June

- August

- November

- December

- All

2022

▾- February

- April

- November

- December

- All

2021

▾- March

- April

- October

- November

- All

2020

▾- April

- May

- June

- October

- December

- All

2019

▾- January

- February

- April

- May

- July

- August

- September

- October

- December

- All

2018

▾- February

- March

- April

- May

- July

- September

- October

- November

- December

- All

2017

▾- January

- February

- March

- July

- September

- October

- November

- December

- All

2016

▾- January

- February

- March

- May

- July

- August

- October

- November

- All

2015

▾- January

- February

- March

- May

- June

- July

- September

- November

- All

2014

▾- February

- April

- May

- June

- August

- September

- November

- All

2013

▾- March

- April

- May

- June

- July

- September

- November

- All

2012

▾- January

- February

- March

- April

- September

- October

- November

- December

- All

2011

▾- April

- July

- August

- October

- November

- All

2010

▾- January

- February

- April

- July

- August

- September

- October

- All

2009

▾- January

- June

- July

- August

- October

- All

2008

▾- August

- September

- October

- November

- All

2007

▾- January

- June

- July

- All

2006

▾- November

- December

- All