Louis Kwechansky and his Chocolate Factory: A Father’s Day Tribute from Alex Kwechansky

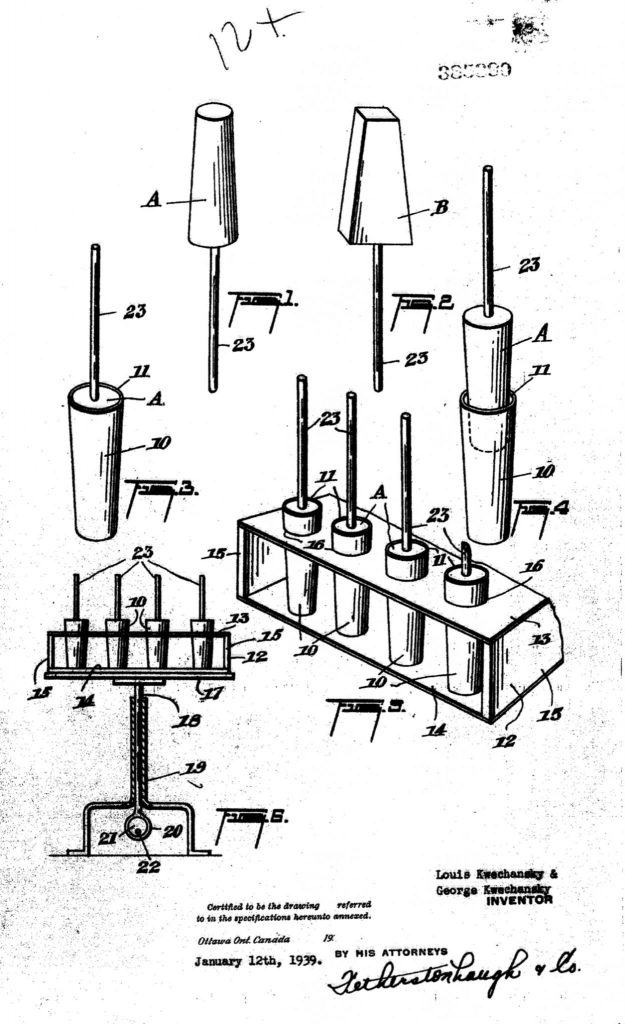

In 1939, well before I was born, my father, Louis Kwechansky was already into chocolate production in Montreal. He had patented a machine to make a product that would seal his fame. He invented a chocolate lollypop on a stick, called a “Chocolate Pop.” He hired the best known intellectual property firm in town to write the patent.

He began making Easter bunnies and eggs in fancy gift packaging and developed Passover fruit jellies and chocolate covered Passover jellies. These candies are still a staple of Passover today.I remember visiting “the factory,” as we called it, during Passover production and a Rabbi would place the “Kosher for Passover” labels on the Passover candies while the Easter candies would flow down those wide fast moving belts just a few feet away. Talk about ecumenical cooperation!

During World War II there was rationing on sugar. Being a prime ingredient of candy, candy companies could still obtain sugar. Consumers would buy hard candy to dissolve in their coffee and tea and the military bought candy for the troops. Times were sweet for Louis and St. Lawrence Candy Company.

The factory had relocated a few times before my time; it grew to between 150 to 200 employees. When I was old enough to go to “the factory,” I cannot recall much excitement over seeing all that candy flowing. It just seemed to be “normal life.” I watched many people working hard, cocoa beans being crushed, belts moving candy everywhere and boxes being filled for shipping. They were supervised by my father’s first and only foreman, Sam Shkarovsky. There was also a supervisor named Carmel, a perfect name for someone who worked in candy.

The chocolate room was one that never diminished in my mind. Many chocolate companies buy chocolate in industrial sized bars from the large suppliers like Hershey’s. Louis made his own chocolate. The beans were imported and poured into three massive crushing drums. They appeared to be about twenty feet high. They were round with a winding staircase going to the top and the top was at least the height of three people.

The process began with crushing the beans. While your taste buds may be wagging at the thought, it is not what you think. The odor (not scent) of this chocolate was acrid and bitter. It would permeate my father’s suits and even our car.

I remember when my father would come home from the factory after being in the chocolate room that day. I would know within seconds of his arrival even though my bedroom was upstairs and far from the front door. But, from that point, things became much sweeter.

They would blend the crushed and refined beans into chocolate liquor. They added cocoa butter as well, lots of sugar and milk when called for. They would blend the mixture to suit the taste that their customers liked. He taught me that dark chocolate would be more caloric than milk chocolate because it needed more sugar to make it edible. The company made chocolate bars, chocolate pops, chocolate bunnies and many items that I do not recall. They developed several trademark brands along the way.

Handling chocolate was more difficult than hard candy due to its low melting temperature. Shipping chocolate was far more difficult in summer than winter. Air conditioning and refrigeration trucks were not an option at that time so heat and humidity were major factors. Humidity was at its highest in August and working was very wasteful. My mother developed the idea that the entire factory would close for two weeks vacation at that time and reopen after Labor Day when heat and humidity would subside. Thus, August vacation was born.

I once asked my father how they controlled the inventory from being pilfered during production. He explained that they did not use any controls during manufacturing. He allowed the employees to eat all the candy they wanted. The secret was that new employees would gorge on candy all day, the first day. All that candy would give them a stomach ache they would not soon forget. The second day onward, they could not stand the taste of candy. Simple, smart and efficient.

As a kid, if I asked for some candy he would bring home a box of candy, usually chocolate pops. To the consumer, a box of chocolate candy might be five or ten pieces. To the son of a candy manufacturer, it meant a box of a gross (twelve dozen, a minimum shipping box). With so much candy sitting in the pantry and as much as we wanted, it lost its glitter. My mother would get upset, to put it mildly, when I would pay money to buy a chocolate bar from another company.

Personal weight control was never an issue. We never overate candy as it did not have the restrictive attraction it has for others. My friends, much later in life, recall how their eyes would bulge when I opened the pantry door and gave them candy when they visited. During a conversation nearing the end of a Bar Mitzvah party in Montreal in 2004, many years after the end of the company, some folks began reminiscing about “the factory.” They were kids when they visited. Though now middle aged or seniors, they sounded like children when they recalled the toffee being stretched, the candies flowing along the belts, the scents of all those chocolate pops, black balls, honeymoons, “chicken bones” (made with crystallized chocolate), marshmallow bananas and so many other treats. I never knew it was so warmly remembered.

Louis was born into the candy business; he began his life in the Ukrainian Shtetl of Rzhyshchir in a region 75 km south of Kiev. The name appears to be Polish and, at that time, Ukraine was alternately under Polish and then Russian control.

His parents made their living making and selling hard candies in the town. As it turns out, that region is a sugar beet growing area. To those who are confused, sugar beets and sugar cane yield the same tasting sweetener though Hawaiians bristle at such comparison. This business supported the family through the Pogroms and the 1917 Russian Revolution. After the Revolution, the Communist government demanded that the Jews in the area relocate to Kiev. That seemed to be the end of Louis and the candy business. However, sometime before 1925, at age 19 or 20, Louis, the youngest of approximately 10 children, left home.

He found his way to Moscow and got a job in a chocolate factory. There he learned what he needed to make both hard candy and chocolate candy. With that knowledge in hand he obtained his exit visa (which is another story all together) and made his way to Montreal. His sister and brother-in-law had already reestablished there.

In late 1925 he arrived on the Cunard liner, Ascania, a ship that served the UK to Montreal route. He travelled in Second Class, not Third Class. Louis knew the better things in life even then. Louis could read and write a fair amount of English and was thus able to write his own name on the travel documents and kept his actual name in the way he chose to spell it.

That same year, approximately, he started his candy business. The street that ran through the Jewish immigrant section of Montreal is named Boul. St. Laurent in French and St. Lawrence Blvd. in English. To them it was Main Street. It remained as a Jewish business and shopping area for decades even after those immigrants prospered and moved to the western areas of the city. A presence of iconic restaurants still exists today. It was on this street that he rented a tiny space in the basement of a very small building, as he once pointed out to me when we drove by. He told me he had a stove and a couple of molds to make hard candy. Hard candy is easier than chocolate.

With this, he was in business. For the name, he chose the name of the street where he started, St. Lawrence Candy Company. To many people, naming a Jewish company after a Catholic Saint would seem odd. But, not to the Montreal Jewish community. The family never gave the slightest thought about it being a Catholic name.

Sharing living quarters with his sister, bother-in-law and apparently, his recently arrived brother, he could work, save and put all his available profits back into growth. Louis was well on his way up. Borrowing from banks at that time was not a possibility. The banks did not want to lend to Jews. We hear that the Jews control the banks, wishful thinking.

The factory grew with his labor and planning. When his brother-in-law’s dry goods store failed he took him and his brother into the business with him as the business could now support them all and his later arriving sister. Four siblings, who we know about, emigrated. The others, to the best of our knowledge, remained in Kiev that we know of, and may have been among the victims in Babi Yar. By the time the business was ten years old, it was a force in the marketplace. He was buying up machinery of other companies that had failed during the Great Depression.

From the Maritime provinces to the Western provinces, St. Lawrence Candy was sought by kids of all ages. Not many people get to prosper and be loved and remembered for the work they did and the generosity they shared with the community, but Louis did.

(With thanks to my niece Minelle in Calgary for her efforts to research far back into our family’s history.)

4 thoughts on “Louis Kwechansky and his Chocolate Factory: A Father’s Day Tribute from Alex Kwechansky”

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

-

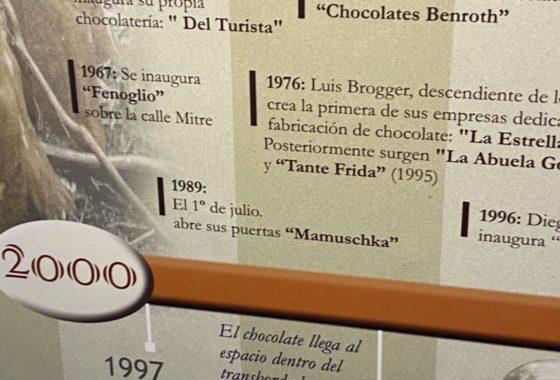

On the Chocolate Trail in Bariloche, Argentina

In March, Mark and I finally extended our chocolate trail explorations in celebration of our special anniversary to Bariloche…via Miami, Buenos Aires, Ushuaia, Antarctica, and Buenos Aires again. There were international flights, a cruise, a couple of domestic flights to get there. All of the travel was amazing, but Bariloche, sometimes called the chocolate capital

Read more › -

Sunday Yeast Polemics: On the Bread Trail

Leavened bread or not? While some of us may think of Passover, the question applied to Eucharistic bread and created significant division in the early Christian Church. The leavened bread for Sunday use was often baked at home by women. Over time, preferences shifted to clergy, church-produced, breads… and, the Eastern Orthodox Church preferred a

Read more › -

Sweet Treat: Chocolate and the Making of American Jews

You may wonder: how did chocolate help define American Jews? Through chocolate, we see that Jews were part of America since its earliest days. Well, since 1701 at least, Jews in the Colonies made part of their living through chocolate. Several Sephardim, leaders of their New York and Newport Jewish and secular communities, participated in

Read more › -

How About Some Uterus Challah?

When Logan Zinman Gerber felt enraged about the loss of reproductive rights in the U.S., she baked challah. Not any challah. She shaped it into a uterus. It wasn’t long after the birth of her daughter that Gerber, a longtime challah baker and staff member of the Religious Action Center of the Reform movement, considered

Read more ›

Some Previous Posts

(in alphabetical order)

- "Boston Chocolate Party" Q&As with Deborah Kalb

- 2022 Media for The "Boston Chocolate Party"

- A Manhattan synagogue explores the rich, surprising history of Jews and chocolate

- About Rabbi Deborah Prinz

- Baking Prayers into High Holiday Breads

- Boston Chocolate Party

- Digging into Biblical Breads

- Exhibit Opens! Sweet Treat! Chocolate & the Making of American Jews

- For the Easiest Hanukah Doughnuts Ever

- Forthcoming! On the Bread Trail

- Funny Faced Purim Pastries

- Good Riddance Chameitz or, The Polemics of Passover's Leaven

- How About Some Uterus Challah?

- Injera*

- Jewish Heritage Month: Baseball & Chocolate!

- Matzah - But, the Dough Did Rise!

- Plan a Choco-Hanukkah Party: 250th Anniversary Tea Party

- Prayers Into Breads

- To Shape Dough: A Trio of Techniques

Archives

2025

▾- All

2024

▾- January

- February

- March

- May

- July

- All

2023

▾- March

- April

- May

- June

- August

- November

- December

- All

2022

▾- February

- April

- November

- December

- All

2021

▾- March

- April

- October

- November

- All

2020

▾- April

- May

- June

- October

- December

- All

2019

▾- January

- February

- April

- May

- July

- August

- September

- October

- December

- All

2018

▾- February

- March

- April

- May

- July

- September

- October

- November

- December

- All

2017

▾- January

- February

- March

- July

- September

- October

- November

- December

- All

2016

▾- January

- February

- March

- May

- July

- August

- October

- November

- All

2015

▾- January

- February

- March

- May

- June

- July

- September

- November

- All

2014

▾- February

- April

- May

- June

- August

- September

- November

- All

2013

▾- March

- April

- May

- June

- July

- September

- November

- All

2012

▾- January

- February

- March

- April

- September

- October

- November

- December

- All

2011

▾- April

- July

- August

- October

- November

- All

2010

▾- January

- February

- April

- July

- August

- September

- October

- All

2009

▾- January

- June

- July

- August

- October

- All

2008

▾- August

- September

- October

- November

- All

2007

▾- January

- June

- July

- All

2006

▾- November

- December

- All

I and my family are your relatives that used to live in Ukraine. In the end of the 1990’s, we moved to America and currently reside in Michigan. I still have the photos that Louis Kvichanskiy sent to your brother. I still have your family photo and the photos from Jennifer’s wedding. If you want to contact me, you can contact me by this email. If you do contact me, I will send you a message to your email with my phone number.

Well done. You must of had a sweet upbringing!!

My mother was born in 1918 in New York City. In 1944 she and my father and my older brother moved to Southern California. One of the few things they brought with them was my mother’s family’s tradition of breaking the Yom Kippur Fast with a chocolate ice cream soda. My mother remembered breaking her fast this way from her first memories of Yom Kippur. I am guessing, from what she and other relatives said, it goes back to at least the very early 1900’s.

It is a tradition that we have not let die. When preparing for the Days of Awe, we always lay in a large amount of seltzer water, chocolate syrup and vanilla ice cream.

As friends and family enter our door following Yom Kippur Havdallah at the synagogue, they are handed a chocolate ice cream soda. Great way to break the fast. It does a great job of chasing away the Yom Kippur fast headache. Here is the recipe:

Pour 2-3 tablespoons of chocolate syrup into the bottom of a tall glass. Add about a 1/2 cup of seltzer and stir. Add two scoops of ice cream and then fill the glass with seltzer. Stir, add a straw and enjoy!

What a wonderful article! Every Passover, my family talks about the Jelly candies that my Zaidie, Sam Shkarofsky, the Foreman of the plant you mentioned made at St. Lawrence Candy.

I have been told that your family was very good to my grandfather and gave him a wonderful career as a “Candyman”.

Thank you for writing this.

Sari Levinson Raskin

Potomac, MD