Chocolate in the South?

This past April we managed a return visit to CoCo Chocolatier, as we settled into Williamsburg, Virginia, for some research about Colonial chocolate at the Rockefeller Library. A break from the data bases of early historical newspapers and library took us to Colonial Williamsburg’s chocolate making day, which occurs the first Tuesday of each month. Food specialist Jim Gay and his co-workers demonstrated the very slow process of roasting and shelling the beans, melting the chocolate with sugar on a stone metate or chocolate stone, as they patiently answered questions and provided historical context. See Mark’s video of the demo

and CW’s official chocolate video.

Traveling on business to the South in 2008, Mark and I had been surprised to find chocolate in the South. That misunderstanding melted away when we enjoyed a decadent outing to the delightful CoCo Chocolatier in Williamsburg’s New Town. CoCo offers fondue, crepes and a good array of fine quality chocolate made by Michel Cluizel, Neuhaus, Knipschildt, Chuao and others.

Through my research I have learned that there was a lot of chocolate in the Colonial Period, though not of the quality we would expect today at CoCo. The formed tablets were often stored randomly and tended to pick up nearby rancid smells. It was also probably wrapped in paper made from rags of varying quality and hygiene. Boxes seem to have been used for larger quantities.

On both trips to Williamsburg we sampled something of this colonial chocolate process and taste in the Mars Company Historic Chocolate line. Several historic reconstruction sites sell it. Its annato flavor and grainy texture may be closer to the less processed chocolate of earlier days, something akin to the chocolate we have tasted in Mexico and Spain, without any of the disgusting possibilities of real colonial period chocolate.

American Heritage Chocolate

I have learned that the cacao trade in the colonial period was pretty significant. For instance between 1650-1750 the influence of the secondary West Indian staples, such as cotton, coffee, logwood, indigo and other dyestuffs, cocoa, tobacco, and vanilla could be as lucrative as the major industry of sugar. Large quantities of chocolate were shipped through the port of NY as early as mid – 17th century. By 1686 New York both imported and exported Venezuelan cocoa. Between 1768 to 1772 New York imported nearly 430,000 pounds of cocoa. In that period, New York shipped 32,318 pounds of processed chocolate to other North American ports. Some argue that chocolate became even more popular in America around the time of the Boston Tea Party of 1773. In 1776 there were 50 or more chocolate makers in the colonies, with 20-25 in Philadelphia. Ben Franklin sold chocolate in his print shop.

Jews were also involved in several aspects of Colonial chocolate as well. American Jewish Historian, Jacob Rader Marcus noted that, “Among the industries in which colonial Jewish businessmen interested themselves was food processing. Jewish shopkeepers specialized in cocoa and chocolate which they secured in large quantities from their co-religionists in Curaçao.” and he continues…“Chocolate in fact may have been a Sephardic Jewish specialty, for the next generation found Isaac Navarro, Daniel Torres, Joseph Pinto and Moses Mordecai Gomez engaged in that industry.” According to Marcus, the very successful Newport merchant, Aaron Lopez, “…saw food-processing as ancillary to his involvement in the coastal and West Indian traffic. Since provisions were the prime staples sent by the New Englanders to the West Indies, it was with the islands in mind that Lopez contracted with various processors for thousands of pounds of cheese, while the chocolate he secured through outwork was destined for local and North American consumption…. ”

Aaron Lopez, pastel, American Jewish Historical Society

Lopez outfitted his ships with chocolate for crews who drank it during their breaks while in port; he shipped cocoa and chocolate; and, he sold chocolate out of his store in Newport. His records indicate that Lopez paid “Negroes” to grind chocolate for him, paying them 4-5 shillings an hour. He also bought ground chocolate from Jews such as Joseph Pinto and Jacob Lousada, who either ground it themselves or also used Negro labor. As early as June 1765 the Lopez ledgers indicate that the Negro Prince Updike ground chocolate in smaller quantities. Indeed within 3 months in 1768, from Feb-Oct, Prince Updike ground over 5000 pounds of chocolate.

Several colonial estate inventories include mention of chocolate, as do those of the Jews. For instance, the Mordecai Gomez estate inventory account of 1750 listed 2 boxes of chocolate (probably paste) at 50 pounds each. The Aaron Lopez estate shows he possessed 50 pounds at the time of his death in 1782.

In 1779 Lopez described the war situation in Leicester and Newport to Captain Anthony, noting that the inhabitants of Newport struggled for provisions. “The Jews in particular were suffering due to a scarcity of kosher food. They had not tasted any meat, but once in two months. Fish was not to be had, and they were forced to subsist on chocolate and coffee.” At least the chocolate helped a bit.

Recent Posts

-

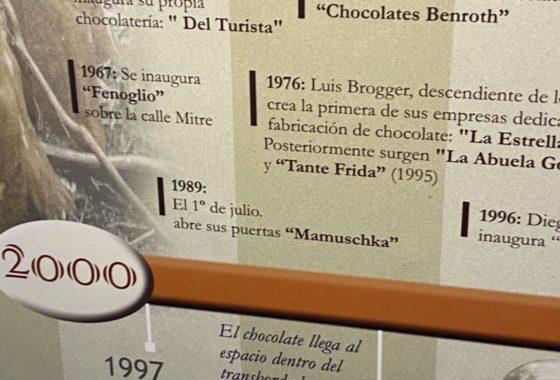

On the Chocolate Trail in Bariloche, Argentina

In March, Mark and I finally extended our chocolate trail explorations in celebration of our special anniversary to Bariloche…via Miami, Buenos Aires, Ushuaia, Antarctica, and Buenos Aires again. There were international flights, a cruise, a couple of domestic flights to get there. All of the travel was amazing, but Bariloche, sometimes called the chocolate capital

Read more › -

Sunday Yeast Polemics: On the Bread Trail

Leavened bread or not? While some of us may think of Passover, the question applied to Eucharistic bread and created significant division in the early Christian Church. The leavened bread for Sunday use was often baked at home by women. Over time, preferences shifted to clergy, church-produced, breads… and, the Eastern Orthodox Church preferred a

Read more › -

Sweet Treat: Chocolate and the Making of American Jews

You may wonder: how did chocolate help define American Jews? Through chocolate, we see that Jews were part of America since its earliest days. Well, since 1701 at least, Jews in the Colonies made part of their living through chocolate. Several Sephardim, leaders of their New York and Newport Jewish and secular communities, participated in

Read more › -

How About Some Uterus Challah?

When Logan Zinman Gerber felt enraged about the loss of reproductive rights in the U.S., she baked challah. Not any challah. She shaped it into a uterus. It wasn’t long after the birth of her daughter that Gerber, a longtime challah baker and staff member of the Religious Action Center of the Reform movement, considered

Read more ›

Some Previous Posts

(in alphabetical order)

- "Boston Chocolate Party" Q&As with Deborah Kalb

- 2022 Media for The "Boston Chocolate Party"

- A Manhattan synagogue explores the rich, surprising history of Jews and chocolate

- About Rabbi Deborah Prinz

- Baking Prayers into High Holiday Breads

- Boston Chocolate Party

- Digging into Biblical Breads

- Exhibit Opens! Sweet Treat! Chocolate & the Making of American Jews

- For the Easiest Hanukah Doughnuts Ever

- Forthcoming! On the Bread Trail

- Funny Faced Purim Pastries

- Good Riddance Chameitz or, The Polemics of Passover's Leaven

- How About Some Uterus Challah?

- Injera*

- Jewish Heritage Month: Baseball & Chocolate!

- Matzah - But, the Dough Did Rise!

- Plan a Choco-Hanukkah Party: 250th Anniversary Tea Party

- Prayers Into Breads

- To Shape Dough: A Trio of Techniques

Archives

2025

▾- All

2024

▾- January

- February

- March

- May

- July

- All

2023

▾- March

- April

- May

- June

- August

- November

- December

- All

2022

▾- February

- April

- November

- December

- All

2021

▾- March

- April

- October

- November

- All

2020

▾- April

- May

- June

- October

- December

- All

2019

▾- January

- February

- April

- May

- July

- August

- September

- October

- December

- All

2018

▾- February

- March

- April

- May

- July

- September

- October

- November

- December

- All

2017

▾- January

- February

- March

- July

- September

- October

- November

- December

- All

2016

▾- January

- February

- March

- May

- July

- August

- October

- November

- All

2015

▾- January

- February

- March

- May

- June

- July

- September

- November

- All

2014

▾- February

- April

- May

- June

- August

- September

- November

- All

2013

▾- March

- April

- May

- June

- July

- September

- November

- All

2012

▾- January

- February

- March

- April

- September

- October

- November

- December

- All

2011

▾- April

- July

- August

- October

- November

- All

2010

▾- January

- February

- April

- July

- August

- September

- October

- All

2009

▾- January

- June

- July

- August

- October

- All

2008

▾- August

- September

- October

- November

- All

2007

▾- January

- June

- July

- All

2006

▾- November

- December

- All